By Kyriakos P. Loukakos, music critic – Honorary President of the Hellenic Drama and Music Critics Union (est.1928)

A foreword in memoriam Renata Scotto

Heading to the Rossini Opera Festival 2023 after two Wagner performances at the Bayreuth one was meant to signify a more hilarious musical atmosphere after the gloomy one of Wagner’s Der Fliegende Holländer and Tristan und Isolde. The latter had been overshadowed by the almost last-minute cancellation of American tenor Stephen Gould, the eponymous hero of the work, a cancellation due to a fatal illness as we were in the meantime informed by a social media announcement of this beloved mastersinger himself. Coincidence or not, the first tidings (not merry at all) we received on our cellphone after landing to the Bologna airport was the devastating news of Renata Scotto’s passing. In spite of the awkward and unforgivable time gap in her discography, that deprived us of timely recordings of this great performer at the heyday of her evolution as an all-round interpreter, what remains from her early as well as -relatively- late stage of her career, in studio recordings, official relays and pirated private recordings, testifies amply to her greatness. Scotto was a soprano, who, in spite of some harshness in exposed high notes and a not particularly imposing stage demeanor, could master a wide repertoire from Pergolesi and Cherubini via Rossini, Donizetti and Bellini to Verdi, Puccini, Ponchielli, Catalani, Mascagni, Giordano and the whole lot of the Giovane Scuola, her interests extending even to some Wagner (her memorable Athens «Wesendonck Lieder» and Isolde’s Liebestod), a somewhat belated but intriguing «Der Rosenkavalier» Marschallin or Poulenc’s «La Voix Humaine». She was endowed with a fierce temperament of full and moving lyricism, an exemplary Lied-like, meticulous handling of the sung text and an excellent technique that enabled her to flow from Gilda, Lucia and Violetta to much more dramatic assumptions like Lady Macbeth on stage and Abigaille on records, an audacious choice of Riccardo Muti after her exciting Verdi, Puccini and Verismo lp recitals of the late 1970’s had reinstated her to an amply deserved Diva status.

Eduardo e Cristina in a successful first staging by ROF

The taxi driver that transferred us from the Central Railway Station to our hotel mentioned it. ROF chose to programme for its 2023 season three obscure works by Gioacchino Rossini and, supposedly, this choice had reduced the flow of cultural tourists to Pesaro. Even the lady at the reception desk, who recognized us from previous seasons, was anxious to know more about it, a wish we had no clue to enlighten.

Systematically though, the choice of three early works, presented by a youthful Rossini, thriving not only to achieve but also to maintain fame, between 1813 and 1819, sheds an illuminating light to the composer’s workshop, full not only by commissions of works that have been established, primarily through the invaluable and consistent effort of Rossini Opera Festival, but also hurried commissions that bore either pasticcios or original works, the failure of which led to the reuse of much musical material by the composer for future masterpieces of his.

Following the moderate success of his serious opera Ermione, incidentally to be staged again by ROF next season, a celebratory one due to Pesaro’s nomination as European Cultural Capital 2024, Rossini, in less than a month, proposed Eduardo e Cristina, an opera based on an earlier libretto by Giovanni Schmidt for an Odoardo e Cristina by Stefano Pavesi, adapted for Rossini’s work by Andrea Leone Tottola and Gherardo Bevilacqua-Aldobrandini. For the 26 numbers of this new creation Rossini borrowed 19 from former ones including Ermione and extending to Adelaide di Borgogna and Ricciardo e Zoraide.

The plot refers to the secret marriage of Princess Cristina of Sweden (soprano Anastasia Bartoli) with the young general Eduardo (contralto Daniela Barcellona), its secret fruit, a boy named Gustavo (silent role), and her official engagement to Prince Giacomo of Scotland (bass Grigory Shkarupa). King Carlo of Sweden (tenor Enea Scala), Cristina’s father, initially implacable towards the pair and its infant offspring, is finally placated and gives his blessing to the couple after the meanwhile imprisoned Eduardo is liberated by his confidant Atlei (tenor Matteo Roma) and has faced successfully an attack by Russia!

The opera presents no real musical weakness but its only -albeit vital- one is the almost total lack of stage action. In this respect, Stefano Poda’s all-round production created an imaginary parallel world of encaged, almost nude dancers, complementing the rudimentary stage action of the vocal performers in psychological terms of body theatre and impact-making choreography (the act 1 military march ballet had a visceral, futuristic power and haunts the memory as the visual highlight of the performance!).

Under the baton of rising conductor Jader Bignamini, appointed as the 18th music director of the Detroit Symphony Orchestra in January 2020, the Orchestra Sinfonica Nazionale della Rai served smoothly yet intensively the director’s vision as well as Rossini’s intentions as revealed in the new critical edition by Andrea Malnati and Alice Tavilla. As Eduardo, veteran contralto Daniela Barcellona could understandably not summon the lower range power and fullness of tone as she managed more than a quarter of a century ago at the small New Epidaurus open theatre, but her sound technique and her vast experience amply made up for any vocal deficiencies. A newcomer to ROF and a very impressive one proved Anastasia Bartoli, interestingly not related to the already legendary identically surnamed singer but to another famous Cecilia of the past, being soprano Cecilia Gasdia’s daughter. In this respect we regret our missing the opportunity to attend Bartoli jr.’s recital with her mother as the pianist, one of the main points of interest in this year’s ROF. A temperamental artist, as much on stage as in her interviews, Anastasia is a singer already oriented towards more dramatic vocal aspirations. Nevertheless, she offered singing of welcome belcanto agility, endowed with a healthy strength sometimes missing from Rossini interpreters. Smooth and involved singing from bass Grigory Shkarupa ennobled the failed suitor Prince Giacomo, while tenors Enea Scala and Matteo Roma offered technical feats of coloratura and high lying performance that ascertain ROF’s Accademia Rossiniana as a main nursery for high standards of singing in the future.

Aureliano in Palmira of Wagnerian proportions

With the central Teatro Rossini having suffered damages due to the last earthquakes in the region of Puglia, all three performances of this year’s operatic programming were hosted at the out-of-town Vitrifrigo Arena, the second of them extending to an almost 4-hour duration. Contrary to Eduardo e Cristina, which was the latest of the three (first presented at the Venetian Teatro San Benedetto on April 24, 1819) and derived mostly from earlier musical self-borrowings, Rossini’s Aureliano in Palmira not only was the earliest of the three, presented at the Teatro alla Scala, Milan on the second day of Christmas 1813, but also it is a totally original partition, which was later to become also a victim of cannibalism of its musical material by the composer, material reused in his subsequent Elisabetta, Regina d’ Inghilterra and, more importantly, in his trademark work Il Barbiere di Siviglia.

The libretto, by a mysterious G.F.R., has been credited either to Felice Romani or to one Gian Francesco Romanelli, perhaps a misattribution of Romani’s predecessor, as house poet of the Teatro alla Scala, Luigi Romanelli. Whatever is true, it serves no honour to its author, as it is desperately static, depicting a love triangle among Persian Prince Arsace, his beloved Queen Zenobia of the Hellenistic Syrian town of Palmira, who reciprocates his love, and her wishful suitor Emperor Aurelianus of Rome. The plot consists of a series of love exchanges between the lovers, interventions by the Emperor and a series of defeats for Arsace, who uses desperately every opportunity to oppose anew to his rival to no avail, with the latter magnanimous enough to grant a happy ending to work, albeit totally deviating from historical facts.

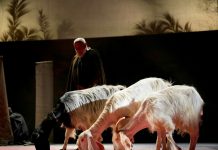

The 2014 ROF production by Mario Martone, revived for the Arena by Daniela Schiavone, stresses this point literally at the conclusion of the opera, which was performed absolutely complete by the local Orchestra Sinfonica G. Rossini under the alert and meticulous baton of Greek conductor George Petrou, who exhausted his considerable talents to provide interest to often inconclusive longueurs of the work. The production offered scenery of almost cinematic realism and lure, particularly a pastoral depiction hosting goats on stage. As for the music, in spite of a few delectable brief love duets, of which the act 1 one was particularly praised by Stendhal (who had the benefit of being exposed to its beauty in the frame of a Paris concert) among several interesting pages, it lacked nevertheless the necessary cohesion to bring matters forward, not strange if one considers the quality of a plot that outstayed its welcome to such an extent of tedious repetition.

The role of Arsace was the only one Rossini ever composed for a castrato, namely Giovanni Battista Velluti, a star of his time but maybe also a culprit for the moderate success of the opera due to his vocal problems during the first round of performances, although he was also the focal point of further revivals in the 1820s and -30s. With good and credible boyish looks, mezzo-soprano Raffaella Lupinacci was a model for the role of Arsace vocally and histrionically, pairing admirably with the perfectly agile high soprano of Sara Blanch for the consecutive love duets, reminiscent of the much more elaborate and extensive ones for a later Arsace and his incestuous beloved Semiramide. On the other hand, we can barely blame either tenor Alexey Tatarintsev for a vocally healthy and masterful yet all-round less than interesting impersonation of the eponymous emperor, or the seconda donna Publia (Marta Pluda), in unreciprocated love with Arsace, for the low impact of the uninteresting, dutiful aria di sorbetto Rossini provided her. All in all, a revival that would perhaps benefit from a more condensed performing version than the critical one.

Adelaide di Borgogna – worthy of reassessment?

It is perhaps not insignificant that the third Rossini opera presented by ROF in its 2023 edition, Adelaide di Borgogna, ossia Ottone Re d’ Italia, followed La Gazza Ladra and Armida and preceded Mosè in Egitto, in other words it emanated from a fruitful creative phase of his career. It says also much, that this secondary work became such an instant and decided flop, a historical verdict that, vis-à-vis its most recent revival in Pesaro deserves perhaps a degree of reevaluation. Premiered at the Teatro Argentina in Rome on the 3rd day of Christmas 1817, the work shares with the two presented last August at the Vitrifrigo Arena an extremely uninteresting libretto by Giovanni Schmidt and equally uninspired musical contributions by fellow composer Michele Carafa, due to its hasty composition. The plot, taking place round 950 a.D., concerns the almost violent pursuit of Adelaide of Burgundy (soprano Olga Peretyatko), widow of the rightful King Lothario, by his murderer King Berengario of Italy (bass Riccardo Fassi), who seeks a marriage of his son Prince Adelberto (tenor René Barbera) with her in order to authorize and consolidate his reign. The Queen implores the assistance of German Emperor Ottone (mezzo-soprano Varduhi Abrahamian), the monarch falls in love with her, prevails over the usurpers and leads Adelaide to the altar as his Holy Roman Emperess-to- be.

As it occurred with Eduardo e Cristina, Arnaud Bernard, a director well known in Greece, chose to overlook the falsified and therefore rudimentary historical frame of the action presenting it as a performance within a performance, an evasive way that worked for this opera, assisted by its comparative brevity. This realistic action, although peppered with often debatable humor and devoted mainly to backstage love quadrilles of the protagonists, found its apex in a politically correct finale, transforming the imperial marriage, sanctioned by high rank clergymen, to a same sex one between the two female protagonists. The offstage activity included the fortepiano and the accompanist Michele d’ Elia, interacting with the Orchestra Sinfonica Nazionale della Rai under the vivid and robust conducting of the experienced Francesco Lanzillotta.

A main point of interest of the present production, the 3rd in Pesaro since its 2006 and 2011 predecessors, featuring Daniela Barcellona as Ottone in both and with Jessica Pratt succeeding to Patrizia Ciofi, was the return to ROF of Olga Peretyatko, an artist much appreciated by its regulars. She enacted and sung defiantly her title role, fearless in her coloratura mastery and ever the bête de scène we recalled from her other assumptions. Ottone, her heart’ s and throne’ s conqueror, was impersonated, vigorously and with the tonal opulence we retained from her Arsace in Semiramide, by Varduhi Abrahamian, a really special singing actress with a rock-solid vocal mastery and an imposing stage presence. The latter is not an asset of René Barbera in the anyway unpleasant role of Adelberto, but this shortcoming was amply compensated by his mellifluous singing, masterful even in the highest lying and florid passages of his demanding contributions, thunderously rewarded by the audience. Italian bass Riccardo Fassi was a decent Berengario. As in Aureliano in Palmira though, supporting roles’ competence, namely mezzo-soprano Paola Leoci as his wife Eurice as well as tenors Antonio Mandrillo as Ottone’s officer Ernesto and Valery Makarov as Adelaide’s adjutant Iroldo, was curtailed by the quality of the music they had to serve, in this case most probably not by Rossini. The vigorous applause though redeemed most of our reservations.

As a programmatic bonne bouche, prior to our first (17/08) and third (19/08) visit to Vitrifrigo Arena, at the coffee time of Mediterranean siesta, we were twice acquainted with the central Teatro Sperimentale of Pesaro, on one side of main Piazza del Popolo. Comfortably seated in a discreetly climatized room, we followed two delectable all-Rossini programs by rising but already established artists, newcomer to ROF light lyric soprano Rosa Feola and the already familiar to ROF devotees contralto Teresa Iervolino. A further promise for next year’s success!